A Christian take on the Affordable Care Act

Presbyterians navigate a thorny debate to find out how God’s children can best get access to healthcare.

by Chris Herlinger

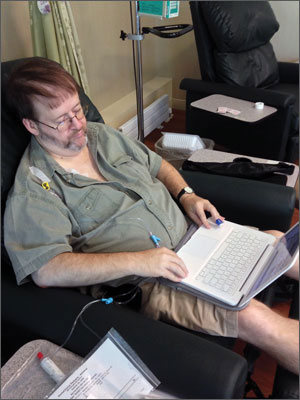

Charles Freeman juggles seminary and chemo. Without his student insurance, he says, he never would have made the visit to the doctor that resulted in the consultation that resulted in the colonoscopy that revealed his cancer. Freeman, who has since graduated, now has insurance thanks to the Affordable Care Act.

Deborah Wade feigns that she is no expert on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or the US healthcare system. But within minutes, she is speaking as a savvy, empathetic, and passionate observer of both—their limits, problems, and possibilities.

Before the ACA was enacted, she says, the healthcare system “seemed too often to be a money-making machine for doctors, clinics, and hospitals,” undergirded by costly tests, drugs, and operations. “It was a way to make money rather than a system for helping people improve their health.”

A member of Anchorage Presbyterian Church near Louisville, Wade works as a program coordinator for innovation and community engagement at the University of Louisville School of Dentistry. Before that, she worked as a manager of outpatient HIV/AIDS medical clinics in Alabama and Kentucky, and that gave Wade something close to a front-row seat for some of the last quarter century’s spirited debates on the US healthcare system.

“It’s not perfect, but at least something got done,” Wade said of the ACA, also known, often critically, as Obamacare.

Still, she feels the country is far from achieving what would help provide optimal care—a patient-centered approach.

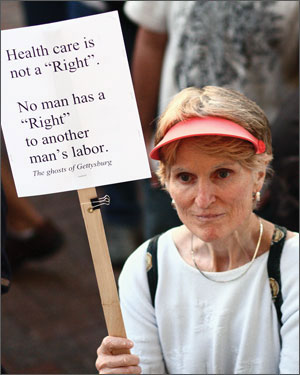

The heathcare debate in the United States has often been heated and divisive. Here, a woman joins other protestors to declare their opposition to national healthcare.

While acknowledging the good the legislation has done—most particularly in getting more Americans insured—Wade is still acutely aware of the ACA’s limits. She yearns for something closer to what she experienced working at the HIV/AIDS clinics—comprehensive, one-stop care that views health problems in a holistic way and does not treat patient problems in isolation.

“Patient-centered care” is something of a mantra for Wade, who plans to begin work shortly toward a second master’s degree, this one in bioethics and medical humanities.

Even with changes brought on by the ACA, Wade sees gaps. “The aging baby boomers like me really need above-the-neck insurance coverage for our ears, eyes, teeth and gums, and brains,” she says. “There is some pediatric care for oral health but rarely any for adults beyond drill and fill and a yearly cleaning. Some of the new health-insurance policies have periodontal care options, but with a $3,000 deductible it is the same as no coverage for most.”

Dental care has not been a subject much addressed in the debates about the ACA, but nearly everything else has been, from high costs and limits of choice to concern about justice and righting past practices.

The debate that won’t end

President Barack Obama signs the Affordable Care Act at the White House on March 23, 2010.

Four years after ACA legislation was signed by President Obama, many are wondering if the nation is done arguing the legislation’s merits and limits.

From the left, the legislation has been attacked as half-baked—doing good for those who were once uninsured and providing a safety net for those with preexisting medical conditions. But some argue that the ACA does not go far enough along the route of a single-payer system that many believe is fairer and would prove to be less costly.

From the right, the legislation has been criticized as creeping, inefficient socialism that will limit patient choice and perhaps quality. And some critics remain defiant and are hoping, through court cases and possible legislation, that the ACA (or at least parts of it) can be repealed.

To date, the US Supreme Court has left major provisions intact, though lower courts are still debating other provisions.

All parties can agree that the rollout of some of its major provisions in early 2014 was badly managed. Still, public opinion polls have shown slow but steadily growing support for the ACA.

What is undeniable is that the legislation has provided health insurance to some 20 million Americans who did not have it before. The overall percentage of those who don’t have some kind of healthcare protection has dropped from nearly 20 percent to about 13 percent.

Another undeniable point: While lawsuits and court cases are likely to surround the legislation for years, opinion polls have also shown that a majority of Americans think the issue has been settled and that it is time for the country to move on and see how things work out.

People gather in West Hartford, Connecticut, to express their differing views on healthcare reform in the United States.

Christian healers

Many Presbyterians, however, don’t seem to have received the memo. They have no interest in going quietly along as the next chapter of the US healthcare system is written.

They are members of a denomination that has a long record in pressing the need for a justice-based approach to healthcare. An option for publicly funded healthcare was long pushed within the denomination, such as when the Clinton administration tried, unsuccessfully, to enact healthcare reform two decades ago. “And in 2008,” says Ginna Bairby, managing editor of the online social justice journal Unbound, “the 218th General Assembly took a step further and endorsed the principle of a single-payer system that, like Medicare, would be privately provided but publicly financed.”

That was the position many church activists pushed during the more recent debates, notes Chris Iosso, coordinator for the Advisory Committee on Social Witness Policy. “For a lot of activists in the church, that [single payer] was the hope,” he says. And it is a living hope with a long pedigree. The 218th General Assembly (2008) named it a “moral imperative of the gospel” steeped in the memory of a Reformation-era Geneva—where John Calvin praised the government-run hospital as an instrument of God—and the many Presbyterian medical missions of the 19th and 20th centuries.

Left: One of many protestors calling for substantive healthcare reform | Right: A young man holds a sign outside a West Hartford, Connecticut, town-hall meeting to discuss healthcare reform with US Representative John B. Larson.

A tangled web of promise and compromise

A number of Presbyterian observers, including physician Jim Wright and Marvin Lindsay, whose teenage son Ethan is autistic, say they are glad to see the changes, even if they are imperfect. Wright says that after congressional opposition (and intense lobbying by opponents), it became clear that the public option was simply not achievable in the current political climate.

“Given the partisanship and the [available] votes in Congress, this was the best that was attainable at the time,” says Lindsay, pastor of New Covenant Presbyterian Church, just south of Richmond, Virginia. But, he says, the good in the legislation is not to be downplayed; it shows the strength of a political system based on compromise. “It’s important not to let the perfect be the enemy of the good.”

Certainly a popular element of the legislation is that preexisting conditions cannot be used to deny healthcare insurance to potential insurance customers. That is good news for Lindsay and his son. “We don’t know what the future holds for him. Will he work for a Fortune 500 company with a good benefits package? We don’t know. But it’s good that [under the ACA] he doesn’t have to worry about that,” Lindsay says. “All I want for him is a fair shot at anything and being able to use his God-given potential.”

Charles Freeman, who recently graduated from Union Presbyterian Seminary in Richmond, Virginia, and who was successfully treated for cancer while a seminary student, understands the importance of that protection all too well as he begins his search for a church call.

His current insurance, one of the state marketplace plans available because of ACA legislation, has afforded him and his wife some peace of mind during a time of transition that would have been treacherous without health insurance. But Freeman did not feel much hope while the healthcare debate in Congress unfolded. “Watching this issue evoked Calvin: the depraved character of human nature,” he says.

There are caveats, though.

The story Jane Givens has to tell is instructive. A former volunteer faith community nurse who remains a consultant to the Presbyterian Health Network, the Michigan-based healthcare worker is among those who believes a single-payer system will eventually come about, but, she says, “not before healthcare gets much, much worse and harder to pay for in this country.”

She relates a story from a report by the United Interfaith Free Health Clinic, with which she has had a long relationship, that reveals some of the gaps with the ACA. Josh, a 28-year-old African American man in Kalamazoo (his name has been changed to protect his identity), was diagnosed with trigeminal neuralgia, a serious nerve disorder that can cause uncontrollable, and unpredictable, pain.

Because of his disorder, Josh has had “numerous visits to the doctor, tests, and MRIs as well as very expensive medication—costs that are not covered by his Blue Cross Blue Shield insurance,” Givens says, quoting the report.

His savings are now depleted by his medical bills, and while he takes medicine, “Josh still experiences debilitating pain in his face and mouth and is unable to work,” she says. He is dependent on his mother—with whom he now lives—for financial support, as he has been unable to receive disability. Even though he now has insurance through the ACA, “it does not cover everything Josh needs,” Givens says. “He will be unable to afford the specialty care (and perhaps a cure) without extra financial help.”

Persisting flaws

Because of these continuing problems, Wright believes a single-payer system will eventually come about. The involvement of private insurance companies, he says, adds unnecessary costs and makes it increasingly difficult for doctors like himself to get paid.

Another factor? The high cost of medical technology, which has nearly overwhelmed the system, says retired Presbyterian physician Ned Bryan, a ruling elder at Starmount Presbyterian Church in Greensboro, North Carolina.

“When in doubt, get another CAT scan or MRI,” he says of prevailing views, which he believes are not sustainable and “will eventually crash and burn.”

As someone who is not practicing medicine now, Bryan is reluctant to speak about the ACA specifically, though he has reservations about its ability to contain costs and believes patients are not immune from some responsibility. “The whole thing has gotten twisted and out of shape and we’ve all contributed to it,” he says, noting patient demands for medical tests some mistakenly believe are free—but never are.

In such an unsettled medical environment—which Bryan characterized as often “bizarre”—Wright in 2006 made an unusual decision to streamline his practice by focusing on seniors and those in nursing homes and practicing only under Medicare, the nation’s federally funded program for senior citizens.

To critics opposed to nationalized healthcare, Wright points out that the United States already has nationalized healthcare, both for seniors and for veterans. While the news has been full of reports of long backlogs at Veterans Affairs hospitals—and several (intentionally concealed) cases of veterans dying as a result—surveys show that most of the more than 8 million veterans who participate in VA healthcare are satisfied. That of course could change as more and more veterans returning from the recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan strain the already saturated system.

Medicare also is often seen as imperfect but still relatively efficient. “It would not be hard to imagine a Medicare type of program for the whole country, but the fact that some of the population already has socialized healthcare can’t even be discussed,” Wright says.

The human margin

A free-clinic truck offers HIV tests on a sidewalk in Berkeley, California. People living with HIV and AIDS (or who are at risk of being infected) are among the most vulnerable in the US healthcare system.

At the core of these debates are often questions of freedom versus justice and of ethics versus effectiveness.

But for Wright and many others—in a country where healthcare costs are second to none but life expectancy doesn’t even place in the top 20 globally—it comes down to a difference between the profit margin and the human margin. Deborah Wade agrees, but says healthcare reform won’t solve everything. Personal responsibility for one’s health is just as important as the system, she says.

While the nation and its nearly 1.8 million Presbyterians continue the debate, one thing, however, is certain: people’s lives are at stake; people like Lindsay’s son Ethan.

Learn more

Earlier this year, Unbound, an interactive journal of social justice published by the Presbyterian Mission Agency, produced “For the Healing of the Nation,” a series of articles offering Presbyterian perspectives and experiences with healthcare in the United States: justiceunbound.org/journal/for-the-healing-of-the-nation.

Ethan is much like other autistic people, Lindsay says—he has highly focused interests (he loves jumbo-sized vegetable hybrids, Christmas, and his birthday) as well as physical and verbal outbursts. “Thanks to a powerful drug cocktail and the coping strategies his teachers have taught him, Ethan is learning to control himself. Without the meds and the teachers, he would have been institutionalized a long time ago.”

The Affordable Care Act was no magic pill for Ethan. His future remains uncertain. But life is a little better than it was before, Lindsay says. “Someday my autistic son will have to buy health insurance, and someone will have to sell it to him. That’s fair. . . . It wasn’t fair that insurance companies could cancel people’s coverage at a moment’s notice or deny coverage based on preexisting conditions. Obamacare ended those abuses.”

Chris Herlinger is senior writer with the Presbyterian-supported humanitarian agency Church World Service.