Our story—and the struggle for cultural diversity

Seeking more than well-meaning welcome for our mixed-race children

By Laura Terasaki

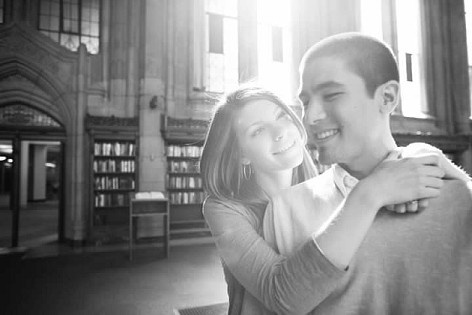

“Konichiwa,” says a well-meaning but misguided congregant to my husband. We exchange glances and cringe. What is intended as a friendly greeting leaves us feeling disrespected. My husband is fourth-generation half-Japanese and fourth-generation half-Caucasian. I am Caucasian and also fourth-generation American, and we are a shining example of interracial marriage in the millennial generation.

Michael and I met in high school and have been together for 10 years (married for three). We have encountered incidents of cultural insensitivity throughout our relationship. An elderly man at a fast-food restaurant once made it clear he was uncomfortable with our relationship. My husband is mistaken for Puerto Rican, Mexican, Korean, Filipino, and more. I’ve been asked what it’s like being married to an “oriental.” We sigh and shake our heads.

Finding a church home has been difficult. Most US congregations are made up of one racial or ethnic majority, and more than 90 percent of Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) members are Caucasian. We have struggled to find a congregation as culturally diverse as our own family. Having grown up in a multicultural suburb of Seattle, racial and ethnic diversity has been the norm in every area of our lives except church. We hope that our future mixed-race children will be welcomed with cultural savvy instead of being made poster children for the church’s attempts at “diversity.”

Rapidly changing

racial landscape

Interracial relationships, sanctioned or unsanctioned, have persisted throughout America’s history (and of course the many coerced through violence can’t be considered relationships at all). Since the end of antimiscegenation laws in the late ’60s, interracial marriage has become increasingly accepted as each generation comes of age. But our generation of young adults is among the first to experience interracial relationships and the hybridity of race as a growing norm. We see the acceptance of racial hybridity in the media with a Cheerios ad featuring a family with an African American father, Caucasian mother, and mixed-race daughter. We see hybridity through Miles Morales, the newest Spiderman, who is half black and half Latino. We see hybridity in athletes such as Olympic speed skater Apolo Ohno, basketball star Carmelo Anthony, or baseball star Derek Jeter. We experience hybridity while dancing to the hits of Drake, KT Tunstall, and Shakira. We see hybridity in political leaders such as Barack Obama, Cory Booker, and Hansen Clarke. As the hybridity of race becomes more normative, many millennials are less concerned with fitting someone into a contrived racial category and more concerned with the power dynamics between the oppressed and their oppressors (power dynamics predicated, of course, on race).

The millennial generation is perhaps the most racially and ethnically diverse generation in the history of the United States. This generation helped elect the first biracial president. But despite all that, segregation and injustice persist. Political issues such as discrimination in the workplace, immigration and the DREAM Act, and criminal justice (think Trayvon Martin) weigh heavy on today’s young adults.

Embracing hybridity as norm

The concept of race has evolved over America’s history. In the late 1600s, social identities began to become constricted and stringently enforced. By 1790, the US census included race for the first time, and naturalization became reserved for whites or Native Americans through marriage or treaties. Racial delineation continued with the three-fifths compromise and the one-drop rule (meaning anyone with one drop of African American “blood” was considered black), and the ideology of manifest destiny and the white man’s burden perpetuated oppression. In the early 20th century, discrimination against Asians, Native Americans, and other minority groups endured as the US Supreme Court allowed naturalization for those who fit “the common understanding of the white man.” In 1977, the US government standardized terminology for race using inconsistent qualifications, with people identified by racial group, historical groupings, or cultural tradition. Not until 2000 did the US census allow Americans to check more than one box under race.

Consequently, those who have been pushed to the margins based on racial or ethnic characteristics inhabit an ambiguous space. It’s a world of the in-between, with tension between the truth of one’s identity and how one is identified by others. For our generation, the perspectives of those who once were oppressed, ignored, or discriminated against are increasingly desired. My generation is beginning to move past the politically correct need for diversity and acknowledge that assimilation cannot continue to be a prerequisite for diversity.

Implications for the church

Although Presbyterians have embraced the goal of diversity for the most part (and in name at least), the potential of this goal has not been realized. As lines of ethnicity blur and the percentage of mixed-race families grows, how can a denomination that is more than 90 percent Caucasian create a church where all are truly welcome?

There are signs of hope and opportunity. The 1001 New Worshiping Communities movement has encouraged new racial-ethnic and multicultural church plants and ministries. Seminaries are preparing ministers for the rapidly changing world. Young adults have formed the Presbyterian Cross-Cultural Young Adult Network to discern, advocate, and celebrate different cultures and traditions in our denomination.

Christian millennials want to be more than diverse individuals hanging out in the same place. We want to be reconciled and embraced for who we are. We seek spiritual spaces where intercultural relationships are fostered and conflict is accepted as a part of our learning process together, not avoided for fear of discomfort or the idolatry of political correctness. We want to be a part of congregations that reflect the makeup of the neighborhood while seeking justice for the oppressed in our midst.

After talking with my husband on this subject, I realize that, although I have prided myself on my cultural intelligence, I too am complicit in this system of privilege and inequity and have committed some of the same mistakes we observe in others. Racial reconciliation is a process, and I have been part of the problem. I, like many in my generation, am learning to listen more, empathize more, recognize power dynamics, and discern how to break cycles of systemic injustice.

As society’s understanding of identity continues to evolve, let us continue seeking the full embodiment of Galatians 3:28, “There is no longer Jew or Greek, there is no longer slave or free, there is no longer male and female; for all of you are one in Christ Jesus,” with fresh eyes and open hearts.

Q&A

In preparing the accompanying article, the author asked her husband, Michael, his about his experience of race in the United States and in the church.

Laura: How do you respond to the question “What are you?”

Michael: I call myself American, and if people want to know where my ancestors came from, I let them know that some came from Japan four generations ago and some came from Germany also four generations ago.

Laura: How do you fill out forms that ask about race?

Michael: I check the “other” box or multiple boxes (both Asian and white), and when the form says check one, I check more than one because their form is wrong.

Laura: What do you want the church to know?

Michael: You don’t need to take steps to make me feel comfortable; you just need to not make me feel uncomfortable. Treat me like everyone else. Most of us just want to go somewhere where black or white or mixed isn’t taken into consideration. I want to be simply appreciated for who I am.

Laura: How is that different from color blindness?

Michael: Treating someone for who they are does not mean ignoring their race or heritage. Everyone comes from somewhere. You can recognize that and appreciate that without bringing up their race every time you meet them.

Laura: So should people not say anything to you when they recognize your last name as Japanese or when they look at you and can tell that you are not full Caucasian?

Michael: I can appreciate it when people recognize my last name is Japanese. I’m proud of that half of me just as much as I’m proud of my white half. It’s my family history. But there are parts of everyone’s family business that they don’t always want to discuss. Everyone has different levels of privacy, and maybe I would rather discuss my personal heritage with people after I’ve gotten to know them first.

When people look at me, I don’t expect them to ignore how I look; I just want them to be more interested in my work or what my hobbies are—these seem like more interesting things to talk about than why I look the way I do. There is nothing wrong with curiosity, but being asked a question by strangers about something that I can’t change in my appearance can feel like being asked about a huge mole on my face that I’m sensitive about. For me, I’m completely comfortable talking about my mixed race as long as it is relevant to the immediate discussion or context or if we have some level of familiarity with one another.

Laura Terasaki is a third-year MDiv student at Fuller Theological Seminary and is in the ordination process of the PC(USA). She blogs about faith and ministry at lauraterasaki.com.

order the special issue Guide to Young adult ministry and read more articles like this one

_-_good_pres_house.jpg)