Legends at the end of the trail

Native American congregations, though small, labor to transform their communities and heal wounds from the violent suppression of indigenous identity and voice.

by Danelle Crawford McKinney

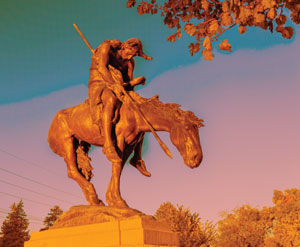

James Earle Fraser’s famous sculpture End of the Trail

(Photo by Shawn Conrad)

On a typical summer evening on the Haskell Indian Nations University campus in Lawrence, Kansas, the activities of the American Indian Youth Council (AIYC) Conference of the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.) were far from ordinary. As many as 60 Native American teens from more than 20 tribes walked silently on a trail named in honor of Billy Mills, a Lakota from Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and the first person from the Western hemisphere to win the 10,000-meter race at the Olympics, in 1964.

The trail took the teens, led by Ron McKinney, a Choctaw pastor from Oklahoma, through preserved wetlands. As they walked in silence, McKinney invited the aspiring leaders to reflect on what times were like only a few generations ago, when communities would travel in the evening to protect themselves from enemies.

Here, 130 years ago, children were taken from their families and brought to this campus when Haskell was an institution whose mission embodied the motto of Richard H. Pratt, founder of the Carlisle Indian Industrial School: “kill the Indian, save the man.” This directive was part of the US government’s effort to “colonize” or “civilize” Native Americans by cutting their hair and stripping them of their language and religious practices. The children buried in a small cemetery on campus are a reminder of documented abuses.

Sitting relaxed in a circle in a grassy area, dressed in long basketball shorts and T-shirts adorned with the names of their favorite players, these teens were in some ways a sign of how much has changed since the founding of Haskell, which later transformed into a tribal-based university built on the self-determination efforts of Native Americans. Some young girls wore shirts with the #23 on them to honor Shoni Schimmel, a member of the Umatilla Tribe in Washington. At that time Schimmel, now a WNBA player with the Atlanta Dream, was just finishing up her college career at the University of Louisville. Her accomplishments there paved the way for young Native American women with dreams of playing college basketball.

In other ways, however, these teens bore the marks of how much has not changed: communities fenced behind walls of poverty, media silence, and violence. Granted, many people in the United States no longer think they need to “kill the Indian,” but that’s only because for them the Indian is already dead—relegated to a romanticized past and sustained only in white memory and cultural appropriation.

In that grassy field, however, one thing was clear: the Native American is alive and complex.

Looking into the faces of those in worship, beyond the muggy scene at Haskell, pastor Buddy Monahan pictured all the small congregations that raised and nurtured these young people. Monahan has been working with congregations as an AIYC advisor to create strong leadership in “Indian Country,” which covers eight PC(USA) synods. The federal government defines Indian Country as land located on reservations. But to Native Americans, Indian Country is a place where you find connectedness with other Native Americans.

Events like the AIYC Conference offer a glimpse of the otherwise hidden efforts of smaller congregations. Some participants come from very isolated places such as the Pine Ridge and Nez Perce Indian Reservations; these small congregations are struggling to keep the doors open and the bills paid, let alone send someone to a conference such as this. Most of these young people have never been to a presbytery meeting or met a presbytery or synod executive.

But just because people don’t see them—or they don’t see each other—that doesn’t mean they aren’t here.

To understand this, take a look sometime at James Earle Fraser’s famous sculpture End of the Trail. It depicts a Native American sitting on a horse while looking down. Many believe that the sculpture depicts a race that is beaten down by atrocities. However, the sculptor said he wanted to express resilience and the “transformation of the people into the next century.” An end, in other words, is a new beginning. Whether you call this place Indian Country or the End of the Trail, Native Americans recognize it as home.

Untranslatable grief

That home is hurting. Smaller congregations in Indian Country face adversity when it comes to serving their communities. Alcoholism has long been present, but it is now recognized as a symptom of a larger problem: the grief of a people robbed not only of economic means but also of their very identity, history, and self-determination. Violence and suicide are also symptoms of this deeper problem that is now being addressed by activists, tribal leaders, healthcare professionals, and clergy.

It is estimated by the US Justice Department that one out of every three Native American women has been raped or has experienced an attempted rape. Native Americans have the highest rate of suicide, more than any other race, in the United States, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. They are also killed by law enforcement at nearly identical rates as African Americans. And across all this violence, more than one in four Native Americans live in poverty; their unemployment level nearly doubles that of the overall population.

The Dakota word iyokiksica (pronounced ee-YO-keek-shee-cha) is difficult to translate but is best described as a deeply embedded grief. Another term for it would be historical trauma or post-traumatic stress disorder. These words are used to describe what Native Americans have been experiencing since the injustices began. While the purpose is not to dwell on these injustices, it is important to examine realistically what ministry looks like in the long shadow of a community’s history. Most of the pastors working in these settings are experiencing the very same disorder facing Indian Country as a whole.

Though the burdens of these communities are great, the impact of these small congregations will have great influence in the healing of the world around them.

Healing practices

A major force on the road to healing is Jim Miller, a Vietnam veteran who struggled at one time with alcoholism. One night he had a vision that he was on a horse leading a ride. So he decided to start a 10-day memorial ride with horses leading up to the anniversary of the largest one-day execution in US history, when 38 Dakota were hanged in 1862 in Minnesota. In 2007 a documentary, Dakota 38, was made to tell this story.

Riders now meet every year at the site at 10:00 a.m. on December 26. In the documentary, Miller speaks as an elder to the Dakota people, calling on them to stop blaming the “white man” and to start a process of healing by reconciling their differences. In 2010 Presbyterian Women learned of this vision and led a campaign to assist the riders with necessities for the 330-mile ride from Lower Brule, South Dakota, to the hanging site in Mankato, Minnesota.

Healing is also being felt near Granite Falls, Minnesota, where Pejuhutazizi Presbyterian Church lost its building to flooding in 2001. With the help of the denomination and various congregations, the church was rebuilt on a higher plane. Since then the community has worked hard to establish a community of Dakota speakers. Walter LaBatte leads worship when the pastor is away at presbytery meetings. LaBatte has also begun a ministry of his own on Facebook. He explains cultural traditions such as growing and harvesting corn (pushdayapi)and writes in Dakota to help others learn the language. Recently, he started hosting Dakota hymn singings at his home. He tells stories and occasionally shares his thoughts on Scripture. His social media presence has drawn a crowd, with young people asking him to tell them more.

Across the country, near Tacoma, Washington, Irvin Porter has become the first Native American pastor for the Church of the Indian Fellowship. This congregation was ready to close its doors when the ministry first revitalized, and it has been busy ever since. A year prior to the AIYC Conference, the congregation began raising funds to help its young people attend. Since then the youth group has grown, and now two youth, Zohndra Hernandez and Pierce Peterson, serve on the AIYC.

Small Native American congregations are also producing leaders for the church. Today, we celebrate the first Native American woman to serve as a synod executive, Elona Street-Stewart, executive of the Synod of Lakes and Prairies. She is an example to many women in leadership.

From horse rides that make sure we never forget to programs that pass along traditions to the nurturing of new leaders, Native American congregations are working to heal grief and recover what has been lost.

Leading into the future

During the American Indian Youth Council Conference of the PC(USA), teens walk through preserved wetlands in silence.

One of those new leaders is Angel Ross, a junior in high school, who was able to attend the AIYC Conference thanks to a scholarship from First Presbyterian Church in Lawrence, Kansas. First Presbyterian collaborated with the AIYC to help another 10 young people attend the conference.

Although Ross is not Presbyterian, she was interested in attending the conference to learn more about the church. “I’m thankful for the support for me to attend the conference,” she says. “I got to meet people I never would have had the chance to meet, and I felt like I was able to help new people see what Kansas was all about.” Angel and the rest of the conference attendees learned about Haskell’s educational programming as well as opportunities through the University of Dubuque Theological Seminary. Both universities make it possible for Native Americans to get an education that they wouldn’t be able to get otherwise.

Today, the AIYC is planning for its next conference in 2017. With new young people serving on the committee, plans are already under way for the youth to learn new skills about being a connected church. Some will travel to the Multi-Cultural Youth Conference at Mo-Ranch, a PC(USA) camp and conference center in the Texas Hill Country, in July. A few will travel to Big Tent 2015.

Leaders in Indian Country look to these young people as the “superstars” of the PC(USA). Some may see Native Americans at the end of their trail, but we are just beginning.

Learn more

To connect with the Presbyterian Mission Agency’s Native American Congregational Support Office: pcusa.org/nativeamerican

Small Native American congregations in the PC(USA) are on the precipice of a new kind of ministry. While leaders such as Billy Mills and Shoni Schimmel change the way the world views Native Americans, leaders such as Ron McKinney, Buddy Monahan, Irvin Porter, and Elona Street-Stewart are changing the way Native Americans view the world. All of them are legends in Indian Country, people who have helped shape who we are. We look ahead to the future of the young people who will be the legends of tomorrow.

Danelle Crawford McKinney is the first Dakota woman to be ordained as a teaching elder in the PC(USA). She serves Native American young adults as the student rights specialist and Title IX coordinator at Haskell Indian Nations University.